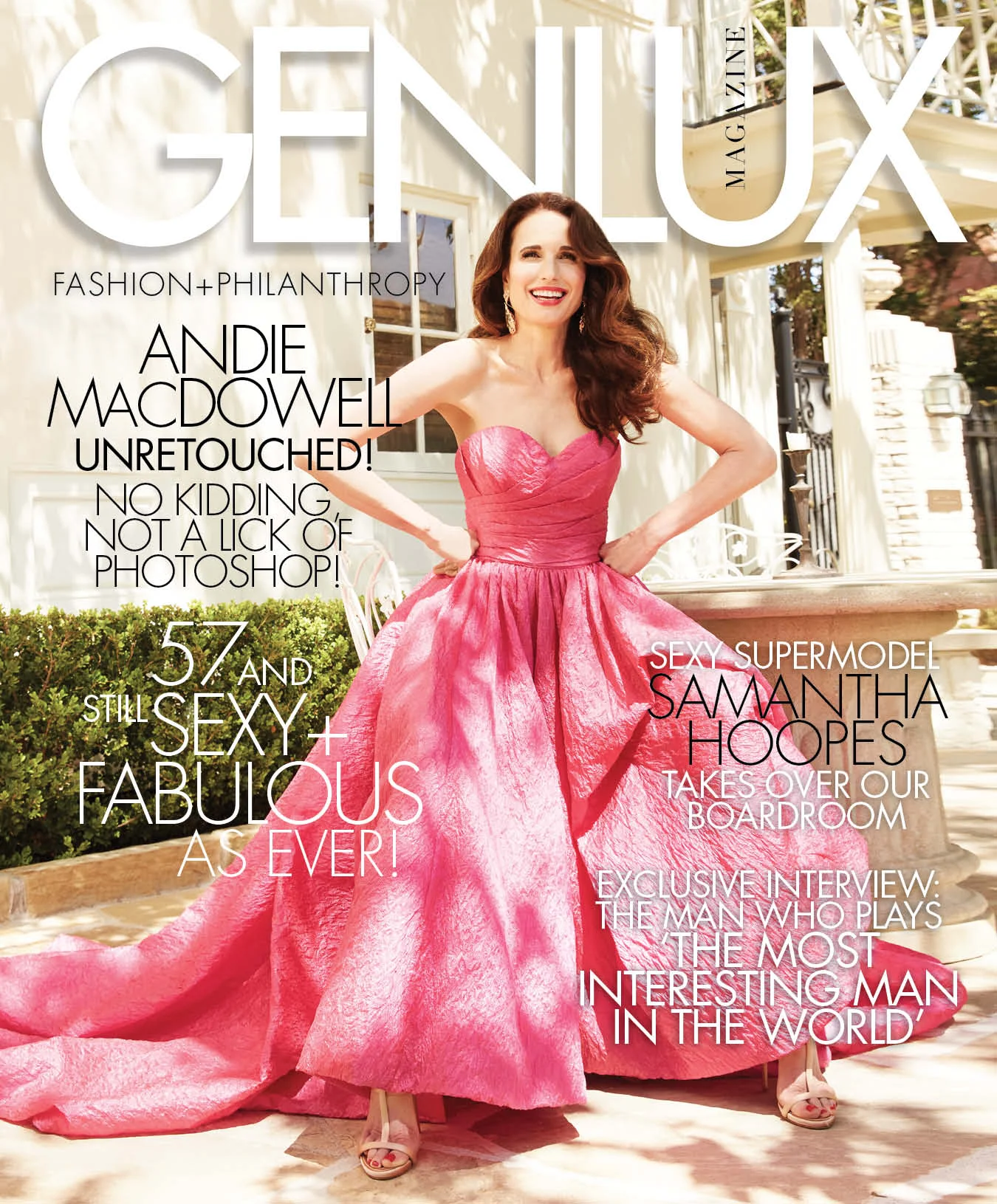

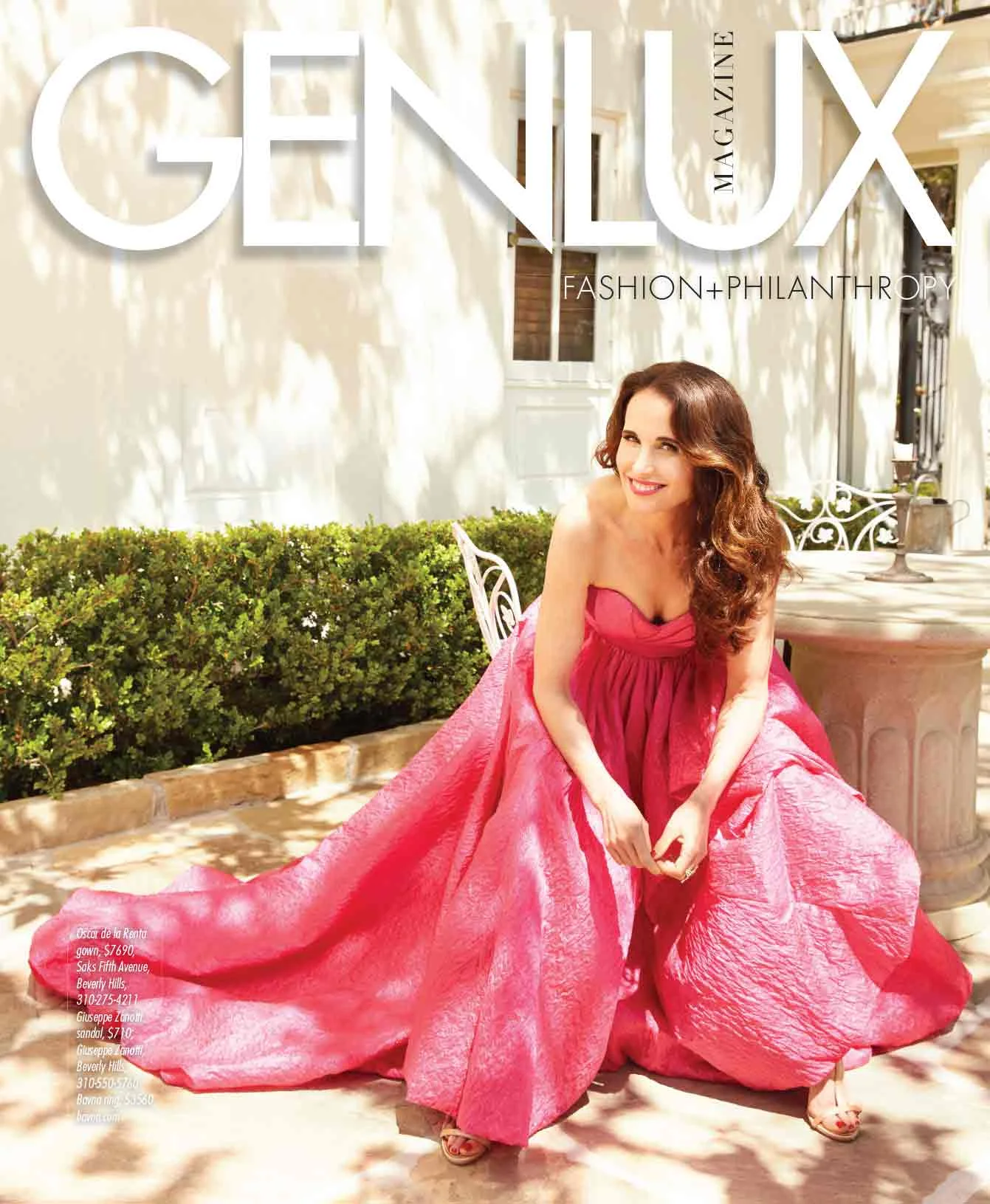

andie macdowell - unretouched

Andie MacDowell is, at 57 (as evidenced by these unretouched Genlux photos) as stunning and sexy as ever. She shares openly with our Stephen Christopher about equality, her heartbreaking childhood, why she downsized her home, and the one thing she’s never told anyone before.

The phone rings and Andie MacDowell’s unmistakable voice—that sweet, lilting Southern drawl that we fell hard for in Sex, Lies and Videotape, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Groundhog Day, Bad Girls, Green Card, and Multiplicity, resonates across the line from Vancouver. She’s there filming Hallmark Channel’s first original-scripted primetime series, Cedar Cove (third season), and stars as Judge Olivia Lockhart.

I break the news to Andie that her Genlux photos are so spectacular—so flawless—we’ve decided not to retouch them. I explain we’re going to run them ‘as is’—not a stitch of photoshopping. “Fantastic!” she fires back, surprisingly unfazed. “Some lines are kind of sexy. Some people say men get sexier with age, but so do women. The idea that men are allowed to get older, but women are not, is an old rule that’s being broken.”

Broken, indeed. Andie certainly makes her own best case. Now 57, she looks nearly half her age. “I know I’m equal and as beautiful and sexy as any man my age,” she says convincingly. “There are a lot of women out there full of vibrancy. Take Jane Fonda. Can you find a man who looks as good as her at 77? I ran into Jane at Cannes. She was preparing to speak at an event that evening, and well, there she was, sitting on the ground like a 16-year-old, writing her own speech. Life’s about embracing your age and having fun—right where you’re at—not where you were before. Of course you’re not that any more. You’ve already been that.”

Even in the beauty biz where young models dominate the landscape, Andie, who’s nearing her record 30th year as a spokeswoman for L’Oréal, is feeling her best years are the present. “There’s an empowerment to where I’m at now. I don’t feel inadequate or that youth dominates me in any way. I feel my experiences and knowledge are cards to my beauty. You get the whole package. Youth can only take you so far. I now have so much more to offer.”

Andie also imparts some of her perennial beauty wisdom: Get a good night’s sleep (at least eight hours), eat organic (lots of fruits and vegetables), be active (ride bikes, takes long hikes, cross-country ski), moisturize (she’s always used L’Oréal Revitalift), and use lots of sunblock. The result? How about not requiring photoshop—even into your late fifties.

Born Rosalie Anderson MacDowell (friends still call her Rose) in Gaffney, South Carolina, she opens up about her unhappy childhood. “My mother was an alcoholic, and my father left when I was only six. My mother was sweet and kind, but I had to take care of myself—and her—my whole life. She had a nervous breakdown right after I was born, and when she came back she started drinking. My childhood was never truly a childhood. I’ve been an adult my entire life.”

At 17, before heading off to college, Andie, forever the responsible one, staged an intervention for her mother at her uncle’s home...but sadly, it failed. Her mother simply would not get out of the car. “I’ve never told anyone this before,” Andie says, putting me on high alert. “My mother had shock treatments when she had the nervous breakdown after having me, so I think she was afraid of what was going to happen if she went inside that house. The doctor came down to the car and said if she didn’t get help, she would be dead in five years—and he was right.”

In 1978, Andie signed with New York’s prestigious Elite Models. The famous one-name models like Esme and Iman were big at the time, but the name Rose was already taken, so the agency decided to call her Mac. Well, that lasted about three days. John Casablancas, the agency president, got wind of it commenting it sounded like a truck, and recrowned her Andie, and it stuck.

With a new moniker and a new portfolio, Andie set off for Paris—and killed it. She worked every day—even weekends—and she loved it. But during this happiest of times, she would receive the saddest letter of her life. “Here’s the heartbreaker,” Andie warns me. “You really want to take out your heart and throw it against the wall? I got a letter from my mother.” Andie pauses, and I can hear her choking back tears, her voice thinning. “She wrote me a letter that said she’d stopped drinking. She quit drinking her last year and told me that she was so proud of me and that I didn’t deserve to have a mother who drank. I was so busy that year I didn’t get to see her. I didn’t go home for Thanksgiving because I was working…and then she died. I still have that letter. I never experienced her not drinking—that was the sad thing.”

Andie’s relationship with her father was no easier. He remarried, and though Andie had desperately wanted him in her life, he wasn’t always available. Then, the year preceding his passing, he was placed in a care facility in Charlotte for dementia and Andie finally had the access she’d longed for. “It was amazing, and we connected and bonded like you couldn’t believe,” she says. “I can’t tell you how healing it was that year to go see him and sit with him and nurture and love him. I fed him and soothed him and comforted him. It healed everything that was broken inside of me. All the pain and hurt that I carried around melted away. More than any other gift I could have received, that was the one—because I wanted and needed and desired his love, but it was something I could never

touch. There’s no greater power than being able to love someone like that. I used to be so afraid of the pain I would feel at his funeral, but when I went, there was no pain.”

Now twice divorced, Andie has three children: Justin, 28, Rainey, 25, and Margaret, 25, with first husband, Paul Qualley. “I talk to my kids about changing and improving. They can improve on me. I let them know, ‘You have that option to make things better. To break patterns.’ And my children know everything about me. We just talk openly and don’t hide stuff. We’re connected in a really deep and beautiful way, and they’re allowed to be their true selves. It’s a constant healing process of changing how families work.”

But if there’s one thing that gets this woman’s goat, it’s this: “I feel equal [to men] even though I’m not treated equal. I’m baffled and confused, because my soul knows women deserve to be on an equal playing field with men. I’m not going to live my life diminished.”

Politics aside, Andie’s ready to rumble for women’s equality her way. “I do like a man who will open the door for me,” she admits. “But if you want me to open the door for you, if that’s what I have to do to get treated as worthy and as valuable, then yeah, I’ll open the door for you. I can still be feminine and equal, I don’t have to start dressing like a man to fight this battle. I can do it in heels.”

When it comes to pitchin’ in, Andie’s all in. She’s been the national spokesperson for both The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund and the American Heart Association. She also put two thousand acres of her Montana ranch in a conservation easement with the Montana Land Reliance (it’s now protected in perpetuity) and she’s also the quickest vetted board member of the National Forest Foundation.

One game changer for Andie came during a visit to a shantytown church in Capetown, South Africa. There, she came face-to-face with severe poverty. Moved deeply, she put her 11,000-square-foot home on the market and downsized to 2,500. “What I saw there blew my mind. Utter poverty. Tears flowed like water out of my eyes—like someone turned on a faucet. My heart just kept breaking open and I had a transformation. I came home and just couldn’t live in that big house any more when the world existed in such poverty.”

As we’re about to jump off the call, Andie pauses and asks if I want to hear the truth about why she sold the house. “The truth is I just didn’t want so many bathtubs. It made me sick to have so many bathtubs that weren’t being used. These people didn’t have a bathtub. I came back and no longer wanted stuff. I’m happier now with much, much less. On such a deep level, sometimes I have this Buddhist part of me that could be happy wearing a purple robe and holding a bowl,” she says, half-joking. “There’s that piece of me that could be really happy doing that.”